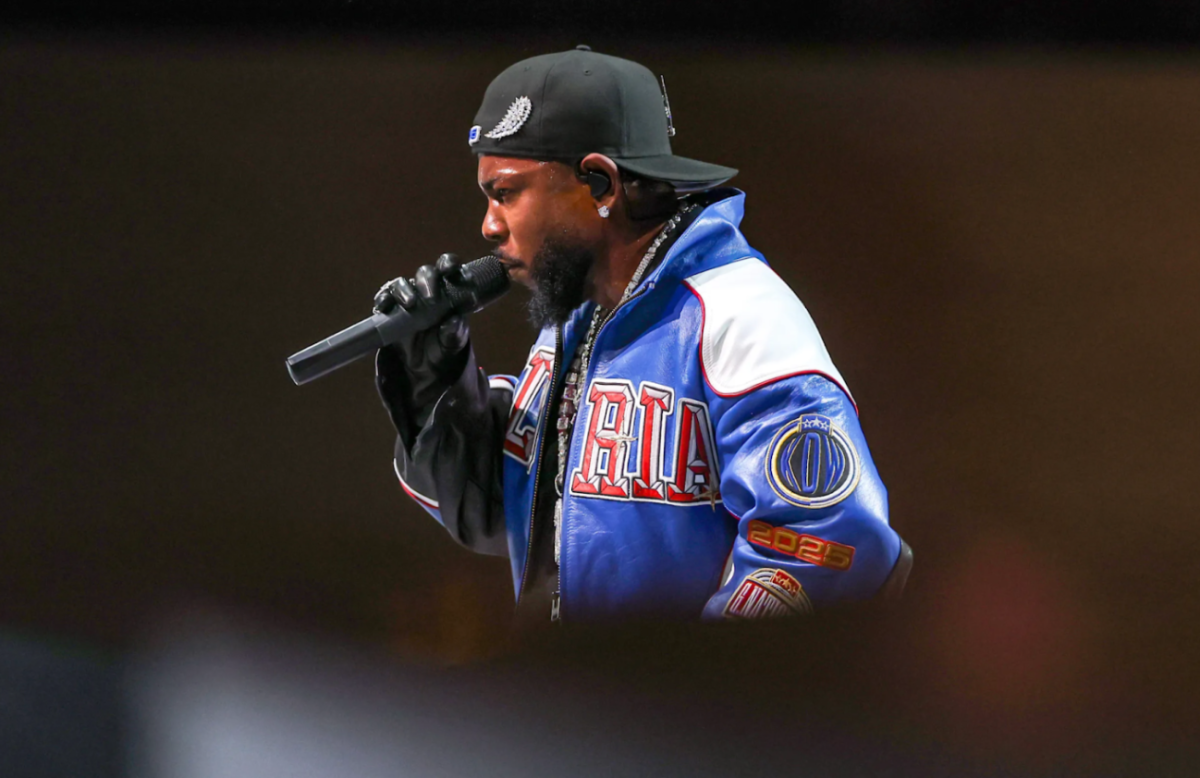

Breland’s Quest to Redefine Country

November 23, 2020

Daniel Breland ’13 goes by his stage name, BRELAND, but he is better known to the Peddie community as D-Breezy.

To many, Peddie’s defining characteristic is its community, and Breland is no exception: his friends from Peddie are some of the best friends that he has to this day.

Breland recalls the Ice House, an open mic night at Peddie, as being an “awakening” of sorts, motivating him to pursue a career in music. Until then he was not “super popular or loud” and he “stayed in his own lane,” said Breland. He had done musical theater in middle school and sung in church, but never produced an original work. This all changed when he and a classmate wrote a song together and Breland decided to perform it. Though he was nervous to sing an original song in front of strangers, everyone loved his performance. “It was a really positive experience,” said Breland. “Everyone was really supportive.” Other students began encouraging him to perform at more events on campus. He felt like “it was the start of something good. [He] wanted to do it more.” After that, Breland became much more focused and began recording music in his sophomore year.

At Peddie, Breland had the space and resources to pursue music at a high level. He would run down to Swig between classes and after the academic day; in a soundproof practice room, he would “just create and explore”, and could even record music on campus. He remembers shooting a “super low-budget music video” with a friend who was pursuing filmmaking, and publications on campus could write about his performances. “It was like kind of a paradise in a way,” he said. “I had a place where I could perform songs after they were written,” as well as the “willing and supportive audience” that was always ready to listen. “I don’t think there are a lot of environments in the world where you have that,” he said. “It was very specific to this type of community [at Peddie].”

The resources Breland had at Peddie were also pivotal: “I had access to everything, and I think access is key when it comes to being able to do something,” he says. “They say you become a master at something when you put in 10,000 hours, and I was able to get a couple thousand hours out of the way in high school.” By the time he was in the music industry and in recording sessions with other professionals, he was prepared with the foundational experience from Peddie.

Breland’s music experience at Peddie was not without its challenges, however. Breland said he “had a mixed bag of performances.” One time, in the middle of a performance in front of the entire student body at a Community Meeting, the music cut out and Breland didn’t know what to do. “We just ran,” he said, laughing. “If that was my very first performance [and it] had gone poorly,” Breland mused, “I probably wouldn’t have kept doing it, or I would have taken some time off.”

But for every botched performance, there were many successes. Breland recounted the Blair Day Pep Rally in his senior year. It was “one of my favorite moments of my whole Peddie career, performance-wise and musically,” he said. “I came out and performed and …it was a really great performance, it was just really high energy”

After graduating from Peddie, Breland went on to double major in marketing and management at Georgetown University. He had gotten into a few different colleges, including the Clive Davis School of Recorded Music at NYU Tisch. “It was a great opportunity but I kind of felt like I had an understanding of the music industry,” Breland said. “If I’m meant to make it in music, I’m going to make it in music regardless of where I go to school.” Georgetown also had an environment and community reminiscent of Peddie, from soundproof practice rooms to the ability to make music in his free time while still growing academically. “I need[ed] a space where I [could] perform in some capacity,” Breland said. With the eventual goal of being able to do music full-time after graduating from college in the back of his mind, he continued to work hard in his free time to make progress in his career. Over a few years. Breland connected with many producers and writers and began to work with them remotely. “They would send me tracks and instrumentals to write to over email and I would write to them and send them back,” he said.

But advancing his career was not all Breland did at Georgetown. “You come out of college with memories, you come out of college with knowledge, and you come out of college with a network,” he said. Knowing that a lot of people at Georgetown were going to go on to do “some pretty incredible things,” Breland wanted to meet and form relationships with as many of them as possible. He started to get involved in everything and make himself a well-known figure on campus. “I was an RA, I was in an a capella group, I was a tour guide, I had internships and jobs while I was on campus, I wrote for the school newspaper, I was involved in the Black Students Alliance,” he said. “I did a lot on campus.”

Throughout his career as a student, Breland made the most of every opportunity he had. Whether at Peddie or Georgetown, he said that he “felt like [he] was leaving having accomplished more than [he had when he] went in.”

Professional Life

By the end of college, Breland had transitioned from being an artist to being a songwriter, as he learned more about the music industry. “As a writer, if I write a really good song and put it out myself, there’s a really big uphill climb to get that song to, say, number one,” Breland said. “And if you want to get a song to number one, you can get it to an artist who’s popular and is getting number ones. At the end of the day, the payout is the same from a publishing perspective.” Calling himself a songwriter made producers more open to working with him. He said it was “a good way for me to meet people and get my foot in the door.” Regardless of what role he played, Breland felt an “urge to be making music and to be involved in music in some way.”

After graduating from Georgetown, Breland had to choose between what he sees as the four ‘music cities’ in America: New York, Los Angeles (LA), Nashville, and Atlanta. New York and LA were “the perennial powerhouses for music,” Breland said, while “Atlanta was and is very much on the come-up.” This, coupled with the many Atlanta-based artists he was working with throughout college, made Atlanta “the place for [him] to go”.

Though Breland now had a plan to enter the music industry, there was a problem in that he had not written any hit songs and therefore was not making any money in music. To pay rent, Breland took the first job he was offered, selling technology for a language translation company. “It was not a job I wanted,” he said. To compete with full-time musicians who were able to write multiple songs a day, Breland would work his day job from 8:30 am to 6 pm, and then stay up until 4 am writing music in a studio. “Something had to go,” he said, “and in that situation, it was sleep and a social life..I ran that cycle for a whole year.”

With the goal of being a musician in mind, he persisted, and this work paid off. After around a year, Breland was able to make music full time. He said, “[I was] able to cover [my] rent every month but I wasn’t doing well. It was a grind, and I’m not ashamed to say this.” For the next year, Breland would often have to fast for the last week of the month because “[he] just didn’t have enough money to make rent and be able to pay for food.” He said that the first two years he spent in Atlanta “were a tough couple of years, but I knew that at some point there was going to be a break and something was going to happen. I didn’t know what it was going to be. I didn’t know what it was going to look like but I just never lost faith that that moment would happen.”

Breland compared trying to succeed in music to being in high school but not knowing when you would graduate. “You could be 50 years old trying to graduate high school,” he said. The difference, though, is that there is no certainty that you even will graduate. “I just chose to believe,” Breland said. “There’s a lot of power in belief…I just adopted the mentality that I wasn’t going to lose. I may be taking small losses now, but I’m not going to lose this war. I’m going to keep fighting day-to-day, week-to-week, month-to-month, and year-to-year, if necessary, until I’ve done it, and then even more after that so I can continue to do it.”

After a year of “writing demos to pitch to artists,” Breland wrote a song called “My Truck.” It started off like “just another demo.” Breland posted a snippet of it to his Instagram and asked for advice and suggestions as to who should perform the song. Some people suggested that he record the song himself. Eventually, Breland decided that if he got 500 comments, he would put the song out. He got the 500 comments in just a few hours. Not expecting much, he recorded “My Truck” and put it up independently on streaming platforms like iTunes, as well as anywhere else people were listening to music. “This was September of 2019 and nothing really happened,” Breland said. He checked back in November, when he was trying to figure out a way to go home for both Thanksgiving and Christmas and make rent, and little had changed.

In the first week of December, though, “My Truck” started to blow up on TikTok, a social media platform.”It was the craziest swing of events,” Breland said. “The numbers started to creep up, and the streams started to go up,” he remembered, “It went from like 10,000 streams to like 25,000 in a night.” Just a week later, “I was getting calls from pretty much every major record label and they wanted to sign me as an artist,” he said. “I signed the deal, got my diploma, so to speak, and from then on, I’ve been out in the real world.”

In addition to a record deal, Breland now has a radio show, was named the face of the Tommy Hilfiger North American Spring Catalog, is performing at the Stagecoach Country Music Festival and the Governors Ball Music Festival, and is working with artists such as Keith Urban. He works on the radio show, called Land of the BRE with his Peddie roommate, Nathan Tempro ‘13. “It’s basically my way of highlighting some of the people on the fringes or on the cutting edge, so to speak, of country music and the people that I feel like are pushing the genre forward,” Breland said. “My hypothesis that I’m exploring or trying to prove on the show is that country music is more diverse and more inclusive than people would like to think.” He is trying to “reshape our perspective on the genre and who’s allowed to participate and who’s allowed to listen to it and why” by defining an in-between space, which he is calling “cross-country,” that includes all of the music that is not strictly defined as country but could arguably be part of the genre based on “what’s being said, how it’s being sung, how it’s produced, or where it was produced.” Cross-country, Breland says, is “necessarily more inclusive because it’s bringing in other sounds, it’s bringing in other perspectives, and it’s bringing in other voices.”

Breland acknowledged this as a perfect time to launch his career, even though 2020 has been filled with unexpected events. “Music has a lot of healing properties,” Breland said. “I would have given up on what I was doing if it wasn’t for the actual music I was making. A lot of those songs never went anywhere but there was something in there that gave me hope. … I think that I have the potential to inspire people. I have the potential to encourage people. I have the potential to make someone smile or make them want to dance. For the two and a half minutes or three minutes that they’re listening to one of my songs or watching me perform they can forget about whatever else is on their mind and enjoy themselves.”

“It’s a really weird time to be having my best year amongst the global worst year,” said Breland.

“Music is in and of itself a powerful thing but I think what makes it even more powerful is all of the other things that it has the potential influence, and I don’t take that responsibility lightly because I know that as quickly as this all happened, it could go away just as fast. And so while I’m working on the stuff that I’m working on, I’m trying to make sure that I’m being responsible with my platform and standing up for different issues as they come up.” Breland makes statements both in his music and using other platforms about important social issues. In particular, Breland is passionate about Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ advocacy, and being vocal about feminism.“ I feel like all of those things are more important than the actual songs themselves. Those are the things that are going to make a difference in the world beyond just one individual listener’s experience.”

“Everything has happened really fast but when I think back to my days at Peddie and how hard I was working even then with no real end goal in mind, I was just working because I loved making music, it’s been really gratifying to be able to see some of the harvest from all of the years that I sowed all my time and energy into it,” said Breland.