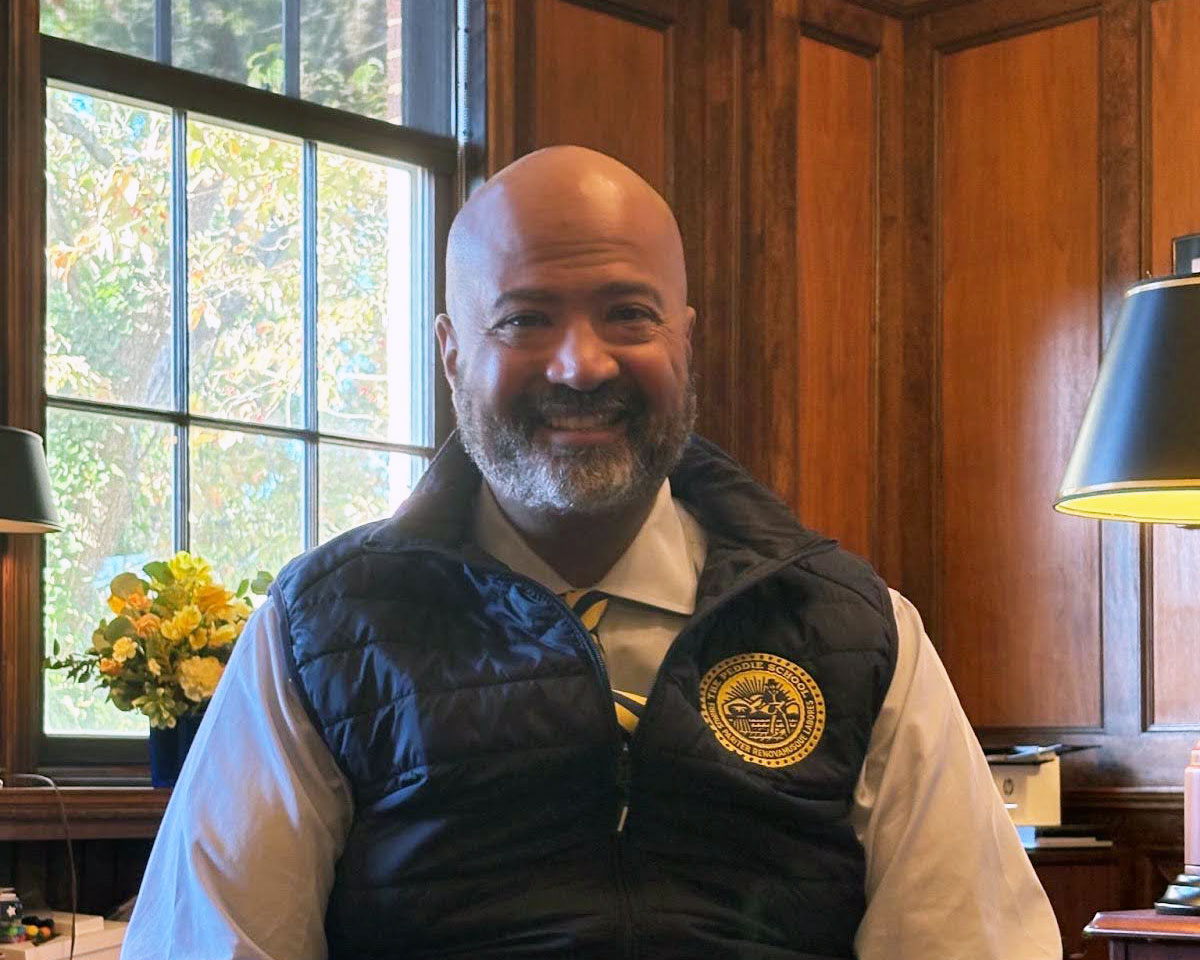

Head of School Peter Quinn: A Day in the Life

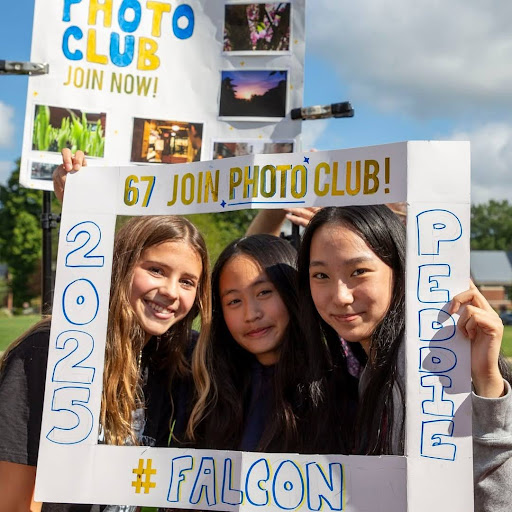

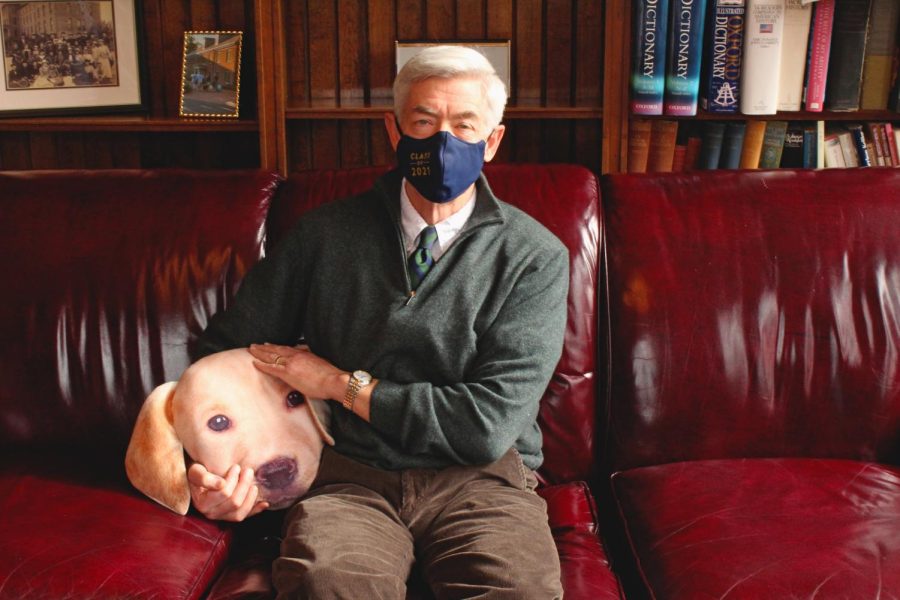

Head of School Peter Quinn poses in his office following his interview.

February 6, 2022

Any Peddie student could easily list off an abundance of details about Head of School Peter Quinn: the bike he jauntily rides around campus, the noteworthy top hat he sports as he walks through Annenberg, his late-night library visits through study hall, even his casual conversations with students about anything under the sun from Barbie dolls to snow dances. But behind the grand doors of his office, students are curious beyond wonder.

Peter A. Quinn grew up as the fifth of six siblings in a family that built themselves around education. With siblings, parents, and extended family all in the business of teaching, a contradiction to their agricultural-based surroundings, it was a given that Quinn would go on following in the footsteps of his scholarly kindred. Accordingly, Quinn enrolled in Washington and Lee University as an English major, knowing full well he planned to pursue his passions in philosophy and language arts.

When faced with the opportunity to join the creative team at Trans World Airlines (TWA) following graduation, Quinn reasoned, “I was an English major, and I was going to be interviewing at the creative department, which was the advertising department, which made sense because I can’t fly. And I’m not an engineer … So I wasn’t going to be in the engineering department! And so I thought, you know, I don’t have a job. I haven’t found a job teaching yet, and I have to do something. English majors can be creative. I can be creative – Yeah, so I’ll try to work at TWA!”

However, upon remembering his first glance out onto the office space, Quinn noted in a downcasted tone, “It was what I would call, a cubicle form … nothing but cubicles.” He added that “all I could see was the tendrils of cigarette smoke. It had to be 500 of these things in front of me. And I remember thinking, ‘I can not come here to work every day. I don’t care what they’re going to pay me, I cannot come here to work.’”

This anecdote from Head of School Quinn’s beginning of his career paints an accurate picture of some of the philosophies he would espouse later in life: A job should not be worked solely for the purpose of achieving an income and fulfilling a duty, just as a decision should not be made solely to mark something off of a to-do list, or just as an education should not be fulfilled solely for the purpose of gaining acceptance to a certain university.

Many moons later, Quinn took this same standpoint when he became head of school. He explained, “If the only thing you think you’re paying all this money for is admission to a college with a brand name, that’s not a very good use of the money, right? Because the majority of this young person’s life is going to be left after you get to college; when you’re out there in the world, being a citizen, contributing to your community. The thing that’s true to Peddie that ought to be our highest priority is how we are teaching the highest quality of citizenship.”

Quinn ties this back to the philosophers he studied in his years as a teacher by introducing a concept by Immanuel Kant: the concept of means and ends. In one aspect, Peddie should be the means of each member’s life. This community looks for progress, and as Quinn said, “I want you to be capable, ethical, and articulate as an adult.” Quinn doesn’t want students and faculty to perceive each experience at Peddie as an end goal. Rather, they should use their Peddie experiences as platforms, or means, for future accomplishments for later in life.

Similarly, Quinn also wants students to treat people, and relationships with them, as ends, as opposed to means. As he put it, “you [all members of the Peddie community] deserve to be treated as an end in yourself.” This means that each person deserves to view their relationships with peers not as stepping stones for themselves but purely to earn the most out of the companionship itself. Quinn questioned, “How many kids have to understand that you have relationships with your community, and with your peers, as an end in themselves. To be good to people as an end in itself is to be good in this community.”

Applying these concepts to optimize the school, he added, “solving math problems, with all respect to the math department, wasn’t the end purpose.” Meanwhile, each class that students take isn’t the end goal of school. Instead, these concepts are what Head of School Quinn aims to teach, for they are the ones that will be applicable ten, twenty, even fifty years into the future.

In terms of the characteristics of great community members, Quinn wishes for his students to be “full of excitement, curiosity and character.” In mapping out these traits, Quinn brought up a past student he recalled singing a song for chapel. The peculiar part of this, however, is Quinn described the student as “a good student, bright guy, very talkative … But not exactly the kind of person you’d think would stand up and sing in front of the chapel.” This is a student who, while recognized as being intelligent, kind and a good person, wass also a bit afraid to get out of his comfort zone.

Yet, something about Peddie pushed him to get up and try something new. As Quinn said, “and the key is that, he didn’t have to do this. No one would have thought, ‘Well, gosh, where was that student’s song?” The student surpassed expectations by applying the character skills he built through Peddie’s influence, and used them to share with the community.

These are the kinds of things Quinn looks for throughout his job. He said, “I think that’s the best part of our lives here. We see so many of those defining moments, mostly from a position of success. Kids put their heart into it. And they do something that no one thought they could do. And sometimes it’s on a small stage. Sometimes it’s just succeeding in physics. But sometimes it’s the song in chapel, or sometimes it’s the goal on the field.” In referencing the example of the student, Quinn added, “It was literal in the sense that it was pretty local. Not going to be headlines anywhere, right? But we had seen him do this, and it reminded everybody, we’d seen a lot of people do this. Now, most of them don’t do it on stage, right? Or most of them, it’s a smaller stage. And to me, that’s the heart of the school. It’s giving people the acceptance to try things that are new to them, and hard for them. And the respect that people around here give to their peers who do something they didn’t have to do, that was somewhat public, and sort of hard. And they do it. And it can be anything.”

Quinn’s ambition in his nine years as Peddie’s head of school has been to help students to accomplish these creations of passion, hard work and effort. Because rooting for one student is like rooting for a school of students, as each student who has created an end in themselves, will thereby become the means for so many more.

So how does Quinn use his job to make all of this happen?

Upon being asked about his days at Peddie, Quinn maintained a modest approach, minimizing his days to “it’s really a series of meetings, interspersed with time to do what I’m supposed to do at my desk.” However, when pushed to detail these meetings, Quinn’s constant influx of problems to fix and decisions to make became clear. He explained, “I am often asked to make decisions because there’s no good choice. Either choice is going to make somebody unhappy, and I have to decide what is the right choice.” With all of the many diverse components of Peddie’s faculty, it takes going through many decision-makers for a settlement to come down to Quinn and his conclusion-making skills, leaving only the hardest of Peddie’s decisions to reach him and a clear answer, just about impossible. As he said, “I’m supposed to make decisions when no one else can make them. Because if someone else could have made them, they would have made them, and they generally do.”

Aside from the decision-making, a lot of Quinn’s meetings consist of outreach and managing the external aspects of Peddie’s community, one of the things that make his jobs so different from any other faculty member. He explained, “a lot of my job, as opposed to when I was teaching, and my job was entirely focused on the kids who are here, a lot of my work is focused outward, helping admissions, working with alumni, helping to hire people.” This also includes a lot of the travel Quinn must do “to connect with people who haven’t been able to come to Peddie,” or trying to learn from “seeing how other people [schools] do something.” After all, just as the students are means for ends, Peddie’s outside alumni and coexisting schools can also be the means for Quinn’s new ideas for his own school.

In terms of ideas, Quinn’s title as head of school, while giving him immense pressure and responsibility, also provides him with the ability to make his own impact on the school and its people.

For example, Quinn brings up the loss of a deep-rooted Peddie tradition, family-style dinners, and his plans to bring them back. Quinn believes that when “we lost family-style, we gave up an important community activity.” It’s important to Quinn that Peddie doesn’t simply resort to continuing with dinners the way they are because Peddie needs a constant drive of community. While it would be easy for Peddie to continue its work passively and leave the effects of Covid to be, Quinn knows that it’s “one of my jobs, my biggest job, I think, to maintain this community as it exists.” For that, Quinn needs to do the work in connecting the aspects of Peddie, for its administration has “got six different departments that have very different personalities, very different goals.” But he went on to explain, “I think my job is to help everyone who runs those programs keep our eye on the school .” This is what brings Quinn to have such a deep impact on this school, for he is the person nailing in the framework that each component of Peddie forms. Through this, he is able to tie the ribbon of our community by intertwining the various aspects into one school.

Quinn also carries his impact to student life. He described interacting with students as “an energizing thing; a great gift, and frankly a bit of a luxury for me.” Still, he manages to create his own lasting effects on the student body, not just through his implements to school, but also directly in his physical interactions. For example, Quinn teaches a summer seminar on the philosophy behind actions and has even taught classes at Peddie when he’s been able to. He is able to serve in student councils and groups and is able to provide advice or support to students when needed. Quinn even takes note of students that his schedule aligns with each term because he “tends to pass the same people in the hall” and wants to remember them.

All in all, Quinn proves to be leaving an indefinite effect on The Peddie School. He combines his love for philosophy with his dedication to bettering the future of all the students in his school. What’s most important, however, is that Peter Quinn has a genuine, pure passion for schooling young people. As something instated in his very blood, Quinn truly wants only the best in all of happiness, accomplishments and civic mindsets of the students. From speaking of third-graders, whose perception of school is “it’s fun!” to fifth-graders, who are “full of excitement; full of curiosity!” to his own high schoolers, Quinn relays there is consistently “an appreciation of each other, and enthusiasm for a being that is youthful.”