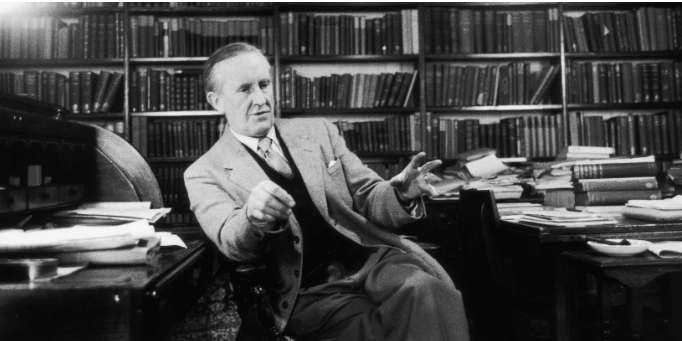

The father of fantasy literature, J.R.R. Tolkien, is most known for his seminal genre-defining trilogy “The Lord of the Rings.” In the wake of their widespread success, they have since been adapted into popular movies which have resonated with fans worldwide. But beyond that, Tolkien has other equally stunning works that deserve recognition. Here, I’ve compiled three works that will introduce you to a wider range of his works — some are readily available online, and I’d highly encourage you to check them out!

- Beren and Lúthien

“Beren and Lúthien” is connected with “The Lord of the Rings” in that it takes place in the same world and tells the tale of the titular characters, Beren and Lúthien. If you know the story of Aragorn and Arwen, Beren and Lúthien are their predecessors. Thousands of years before Aragorn and Arwen were born, Beren the man and Lúthien the elf princess fell in love and became the first of the Half-elven line*.

I won’t spoil it for you, but “Beren and Lúthien” follows the story of their love. Lúthien is an elven princess, and as such, her father sets an impossible dowry for Beren. Together, however, Beren and Lúthien are able to survive against the perils set against them. In this moving tale, Tolkien draws the greatest love story of Middle-earth for the reader to breathe and witness. It’s truly one of his most beautiful works, and is great for extended reading for those who are already familiar with “The Lord of the Rings.”

“Beren and Lúthien” is available as a truncated version in Tolkien’s book of legendarium, “The Silmarillion,” or as a standalone book (which is lengthier).

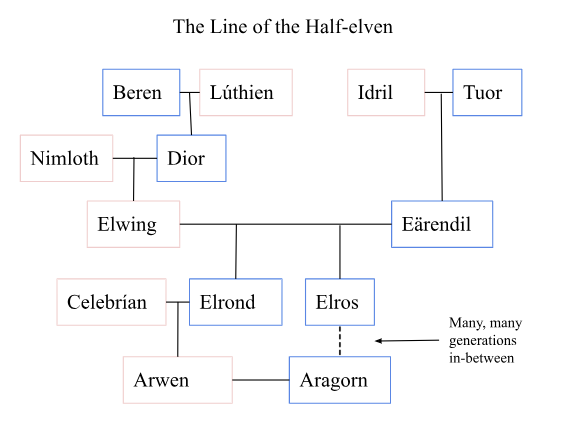

*Fun fact: Aragorn and Arwen are actually related through the line of the Half-elven. There was another example of man-elf union during Beren and Lúthien’s time, Idril (elf) and Tuor (man). Beren and Lúthien’s granddaughter married Idril and Tuor’s son. They then had two children: Elrond, an elf, and Elros, a man. Arwen is Elrond’s daughter, and Aragorn is distantly descended from Elros. So, if we do the math, Aragorn and Arwen are cousins 62 times removed. See the tree below for a visual representation.

- Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics

Outside of his career as an author, for which he is primarily recognized, Tolkien was also professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford University, a title he held for a significant portion of his life. “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” stands as one of his most compelling academic lectures and is one of the defining standards for which “Beowulf” is analyzed in academic circles.

For some context, “Beowulf” is an Old English epic* poem detailing the exploits and heroics of the titular protagonist Beowulf. You can think of it as an Old English version of a text like “The Odyssey” or “The Aeneid.” Tolkien had a deep relationship with “Beowulf.” He wrote multiple essays on it and studied it extensively. It was one of the many sources he used that inspired his own fictional work. In fact, he drew heavy inspiration from the book for his own trilogy — many of the events and characters in “The Lord of the Rings” reference “Beowulf.”

*In his lecture, Tolkien disagrees with the term “epic.” He finds that the focus of the piece should not be on Beowulf’s exploits nor his heroic adventures; rather, the focus should be on Beowulf himself and the poem’s themes surrounding his mortality and inevitable death. He argues that “Beowulf” is not an epic and that there is not actually a term to describe it, but classifies it most closely to an elegy or a prelude to a dirge.

In “The Monsters and the Critics,” Tolkien essentially argues that “Beowulf” has not been treated properly as a work of art and literature; rather, it has been primarily approached as a historical document, which detracts from its inherent literary value and the foundation on which it was built. Tolkien makes a few beautiful allegories explaining this in his lecture (which you can find online), though I’ll explain it in plain terms: Most academic approaches to “Beowulf” only consider its historical, archeological, philological**, etc. contents. They do not actually approach “Beowulf” as a poem, which is what it primarily is.

Tolkien also greatly admired “Beowulf” for being symbolic without being allegorical, a technique he himself tried to emulate in “The Lord of the Rings.” If you are familiar with Catholicism, you will recognize many near-allegorical (but not quite enough to count as an allegory) references to the religion, as Tolkien was a devout Catholic.

In “Beowulf,” Beowulf fights a dragon and some other monsters as well. Regarding the monsters, Tolkien argues that the monsters are central to the poem’s themes of death, mortality, and the final tragedy of the extinguishing of a life. These monsters should thus not be dismissed as examples of cliché or weak storytelling. Though some critics find the poem’s plots and events trite, Tolkien instead argues that the “trite” parts (the monsters) are essential to our understanding and dissection of “Beowulf.”

He analyzes the piece in twos. For example, according to Tolkien, there are two main parts to the story: Beowulf’s exploits and his aging life after them. He also writes about the fusion of old Norse paganism and new Christianity (he writes that the poet is a Christian looking back on a pagan time). He also examines the idea of mortality, which is very prevalent in “Beowulf,” through Norse mortal gods and Roman and Greek immortal gods. He examines the monsters again through this lens.

To spare you from reading through my summary, I’ve given just the bare bones of his lecture. I definitely cannot emulate his academic prowess and striking analysis. Truly, reading this lecture is such an eye-opener, even if you’ve never read “Beowulf” before. To me, it represents the pinnacle of academic and literary analysis. If interested, you should definitely read the lecture and perhaps even give “Beowulf” a read!

**Another fun fact: Tolkien studied philology, which is the study of language in written text, in college.

- Errantry

“The Song of Eärendil” is the longest poem to appear in “The Lord of the Rings” and is composed and sung by Bilbo Baggins while he’s in Rivendell. Long before penning “The Lord of the Rings,” Tolkien wrote a poem called “Errantry,” which he called “the most attractive” of his poems. I mention “The Song of Eärendil” because it and “Errantry” have the exact same poetic meter (Tolkien actually invented this meter himself) as well as similar patterns throughout. Indeed, “The Song of Eärendil” itself is based upon “Errantry,” as the two pieces have deliberately contrasting subject matters. Very interesting!

As a standalone, “Errantry” is a poem that’s very nice to read. Tolkien was right in describing it as “attractive.” It’s a pretty, flowing piece that won’t take long to skim over and is great to compare with “The Song of Eärendil.” I’d say it’s a great starting point for Tolkien poetry (outside of the obvious “not all that glitters is gold” poem) so be sure to check it out if you’re interested in that!

Thanks for reading all the way down! I review things!

Email me suggestions — movies, books, short stories, poetry, food, etc. — at [email protected]

Bri • Apr 29, 2025 at 8:09 pm

Awesome article! More things to add to my reading list.

Couple of years ago I came across a used copy of Beowulf and now I have added incentive to finally read it.

JUSTINE • Apr 29, 2025 at 6:46 pm

Greetings, very interesting article. I remember years ago inmy local library, coming across Tolkien’s book ” Silmarillion: but o never got a chance to read it. I’m more inclined to follow up after reading your article. I loved watching the movies on the “beowulf” tales. I had no idea Tolkien had body of works on the subject. Have a beautiful day! ♥️

Me • Apr 29, 2025 at 12:06 am

Farmer Giles of Ham is a hilarious story about the adventures of a medieval farmer and his talking dog. Does not get enough love from the Tolkien fandom.